Jan Henle: Sculpture of No Thing

by Nancy Princethal

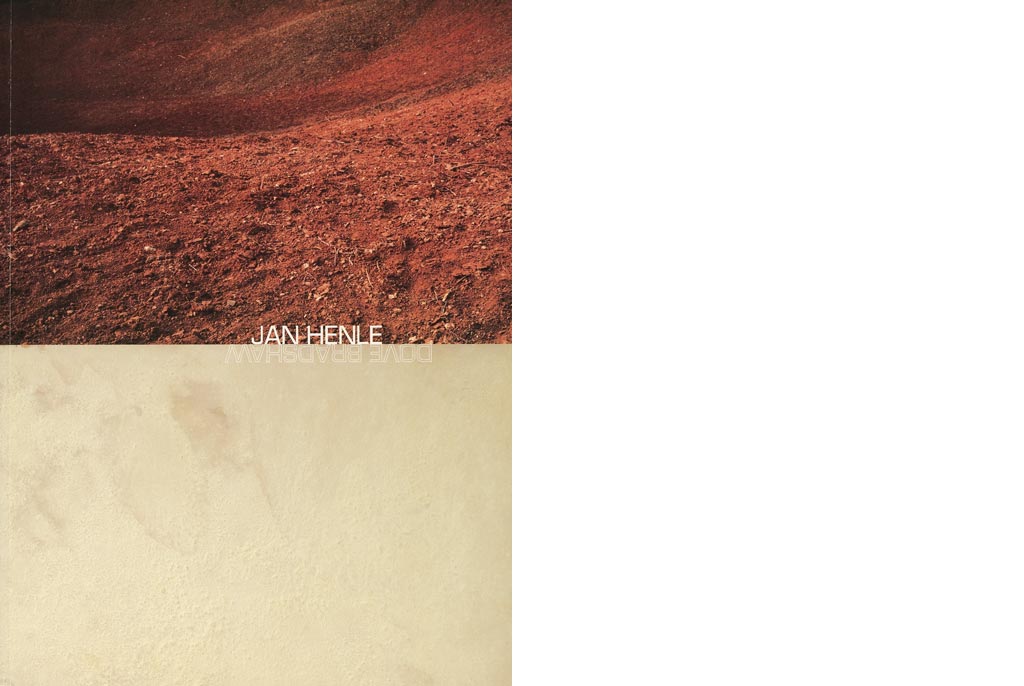

Mayaguez, a small city on the southwest coast of Puerto Rico, is hot and damp, and ripe with the smell of food. Leaving town, the pastel-colored, steel-grilled concrete houses gradually give way to forest. Rural Maricao is an hour out of Mayaquez by jeep, and 1,200 feet up. The road is impossibly narrow, rutted and twisted, and the dense tropical greenery, its huge leaves springing from gnarled, fibrous limbs, crowd close.

As evening approaches, the leaves seem to grow bigger, the road narrower. The hills are absurdly steep and small - a garden-sized wilderness, like trecento depictions of Eden. Unlike the dirty haze of the city, the humidity in the hilltop air of Maricao clarifies it, as water does the inside of a glass. At twilight the forest, ruffled by wind, is easier to hear than see. Legions of insects whir, buzz, and click. Birds call. Tree frogs chirp.

Here, on a hilltop with a distant view of the sea, Jan Henle has built a house. Hardly more than a single room, it is not Spartan (there are all the fixtures of modern life), but it radiates a kind of visual composure.

Nothing is inessential, everything is in its place; serenity prevails. With its narrow, perfectly groomed margin of garden, it is a rigorously tended refuge from the organic ferocity beyond, where plants grow with stupefying speed and vigor, sometimes (the so-called strangler fig is a case in point) as if from midair, sending roots down and vines up in a headlong assault on Northern conventions of biological priority, temporality, and spatial decorum.

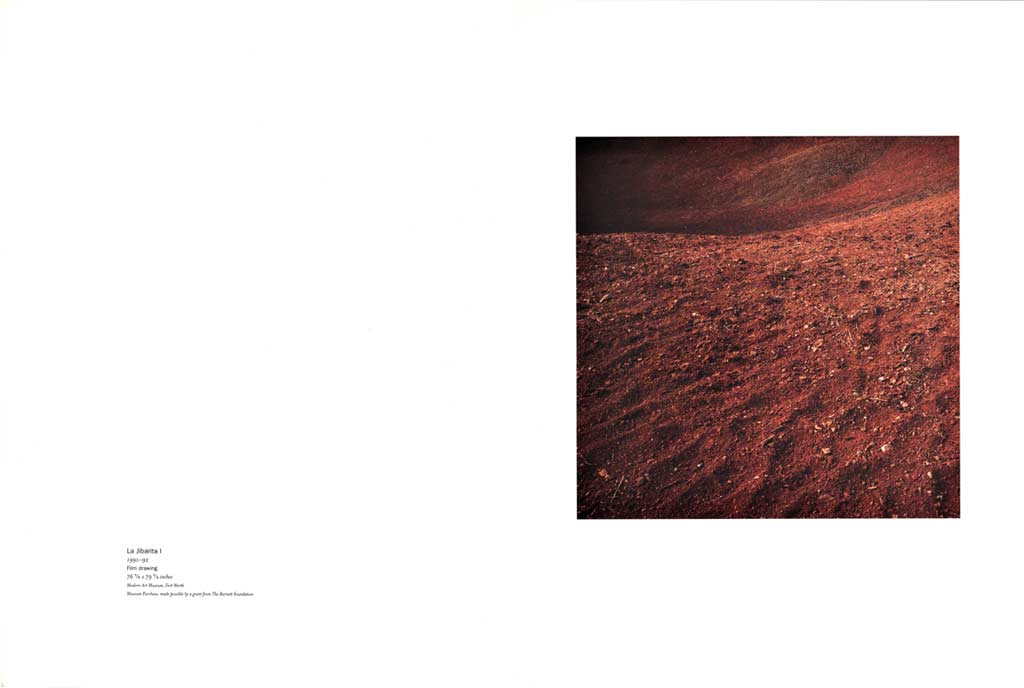

Also here, a few hundred yards away from Henle’s home, is the piece of land, slightly more than an acre, with which he created La Jíbarita. A roughly pentagonal plot, 225 feet long on its longest side, it is steeply inclined, and now thickly planted. But in 1991/92, Henle cleared it down to the ground. Working with four or more local jíbaros, or Puerto Rican mountain men, and relying almost exclusively on hand tools - axes, machetes, and hoes - Henle spent eight months slowly revealing the intensely red, clay soil. The largest stumps were removed by bulldozer, with considerable effort, but the final work was done manually, including covering the machine’s traces. On the last day, a dozen men turned the earth with hoes, creating the deep, rich surface that appears in Henle’s ten “film drawings.” Five of these are the enormous silver dye-bleach images (spliced together meticulously from two or more prints) that appear in the MOCA show, and some have been shown before. But apart from a few close family members and friends, including the workers who helped make it, no one saw La Jíbarita in its sculptural state.

Even viewed cold, without any prior information, the film drawings are overwhelming. Each shows a big fragment of the site, without contextualizing limits. There is no sky, no bordering vegetation. The undulating soil, a vivid, meaty, almost Martian red, is depicted with exacting resolution: every nuance of color and scrap of dried weed stem, every soft rise and fall of the earth, is plainly visible. It is the big things that are easy to mistake - scale, and the steep grade of the slope are very difficult to read. At more than six feet high and hung close to the floor, the film drawings are roomy enough to walk into; in Michael Auping’s description of earlier work, they promote “not so much a sense of looking at the landscape but rather, a sense of being in the landscape.”1

Seeing the local land planted, or left idle--that is, given over to unregulated growth--makes the nudity that Henle created in La Jíbarita seem almost scandalous, sensuous in a way that edges beyond metaphor. Not that the site, or much of the surrounding area, constitutes virgin forest. (The acreage Henle used for La Jíbarita had once been a coffee plantation, and soon after the project was completed, he returned it to productive use, planting mainly coffee, and also banana and pineapple, all with great sympathy for the land’s ecological health; even when cleared, it was protected from erosion with bamboo terracing.) But the aggression and tenacity of the native vegetation gives the interval Henle created—the abeyance, the moment of pause—its ineffable power. The film drawings, named to establish a formal limbo free of photography’s inherent concerns (the word “photograph” is “too conclusive,” for Henle2), are alienated from more than a comfortable spot in the art world. They attempt to transfer an “essence of being,” in Henle’s words, of work that was created to suggest the fullness of life from a gesture of clearance—and that seems the more impossible the more its conditions are understood.

Henle refers to this experience as an approximation of “no thing,” a concept rooted in various systematic and intuitive approaches to understanding the things that, for him, count most: friendship and love, oneness, timelessness. His readings in Zen Buddhism, Christian mysticism, and Native American writings have led him to pursue the quality of enduring, unchanging, and vital emptiness that makes possible an intuition of unity, both internal and with the world beyond one’s skin. Activity undertaken for no material reason, towards an effect that remains invisible, is a guiding principle in Henle’s work.

In traditional Chinese painting, brushwork stands for transient gestures and their subjects, while the blank surface of the silk or paper indicates the “permanence of space,” a void that is also a “spiritual solid”—an equivalence between clarity and clearance that also applies to La Jíbarita. The scholar Mai-Mai Sze has observed of Chinese painting that “Silence and emptiness of space possess vast powers of suggestion, stimulating the imagination and sharpening perception. And only through exercise of these highest faculties can the Tao be apprehended and expressed.”3 Quoting Chuang Tzu, whose writing is very important to Henle, she concludes, “The Tao abides in emptiness.”4 Though affinities can be drawn with Chinese painting, Henle’s practice is closer still to the tradition of Japanese Zen gardens, of which the Kyoto garden of Ryoan-ji (c. 1500), a rectangle of raked white sand punctuated by fifteen carefully selected rocks, is paradigmatic. One observer notes that, in contrast to such Western pictorial representations of emptiness as the lunar landscapes of Yves Tanguy or the silent, shadowed plazas of Giorgio de Chirico, “The vacant space of Ryoan-ji does not evoke a mood of loneliness; it is free of emotional associations. It arouses no thoughts of the absence of man, or of anything connected with human life; nor does it evoke the need to be filled.”5 Again, the qualifications serve La Jíbarita equally well.

The danger (and sometimes the appeal) of Zen for Western artists is that, in its invocation of limitlessness, it can also be used to justify an avoidance of resolution, and Henle is sensible of this hazard. His work, he says, is meant to be “open, but not ambiguous—there’s too much ambiguity in the world.” He values Buddhism as a discipline, rather than an esthetic license. Artmaking, for Henle, is best rooted in humility and in responsive activity, not introspective reflection; rather quixotically, he believes that art can be ethical, and “practiced in life itself.” It is a belief in which Zen can provide support. His acute concern for the ecology of the land he uses and, even more, for the people who collaborate on his projects, reflects that commitment. “The Zen method of spiritual training is practical and systematic,”6 says Daisetz Suzuki. “With the development of Zen, mysticism has ceased to be mystical; it is no more the spasmodic product of an abnormally endowed mind. For Zen reveals itself in the most uninteresting and uneventful life of a plain man of the street, recognizing the fact of living in the midst of life as it is lived.”7 Following Suzuki, the Christian philosopher Thomas Merton writes, “Zen is not theology…nor is it an abstract metaphysic. It…is a concrete and lived ontology which explains itself…in acts.”8 “To suggest that it is an ‘experience’ which a ‘subject’ is capable of ‘having’ is to use terms that contradict all the implications of Zen,” Merton continues. “Zen is not ‘attained’ by mirror-wiping meditation, but by self-forgetfulness in the existential present of life here and now.”9 By stressing experience—physical, perceptual—over product, and immersion in actuality rather than its transcendence, Henle hews closely to the precepts Merton describes.

All connection between Henle’s work and Zen must, however, remain qualified. For one thing, Zen thought is notoriously elusive, to those brought up in it and infinitely more so for Westerners; “From afar [Zen] looks so approachable, but as soon as you come near it you see it even further away from you than before,”10 warns Suzuki. For another, Henle, self-taught in Zen, sustains only an oblique relationship to its teachings. Even in the relative isolation of Maricao, where he is often joined by his wife, Dee Vitale, Henle does not live a life of monasticism, or even strenuous asceticism. He and Vitale also maintain an apartment in New York, and Henle has an abiding and well-informed (if skeptical) interest in the world of contemporary art. It is within that community that he intends his work to make itself understood, however inaccessible it remains, logistically if not conceptually. Indeed, as in Zen, paradox, inner contradictions, even outright inconsistency run deep in Henle’s life and work.

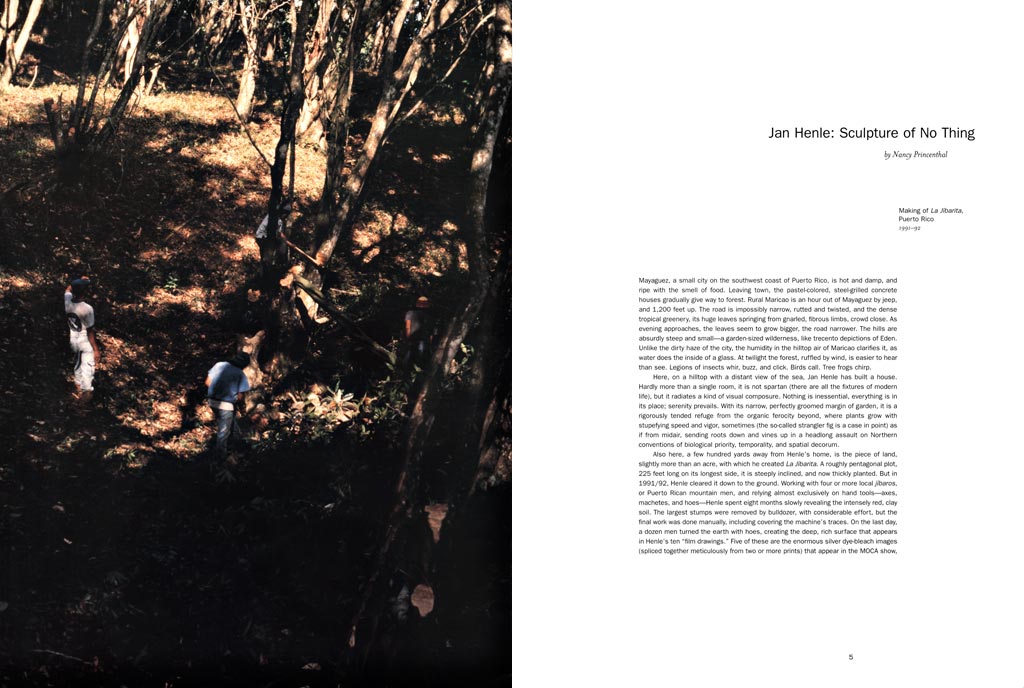

Henle’s crucial involvement with the land, and with the islands of the Caribbean in particular, speaks, for instance, of an equally deep-seated nomadism. Born in New York in 1948, he arrived in Puerto Rico less than ten years ago, in 1989. His first four years were spent in what was then semirural Westchester County, just north of the city. Henle’s father, Fritz, German by birth, was a successful photojournalist and fashion photographer; his mother Atti van den Berg, born in The Netherlands, was a well-known dancer and remains, at eighty-four, a woman of remarkable zest and creativity. When Jan was four years old, his parents separated, and he moved with his mother to St. Croix, a U.S. possession that the family had visited on a photo assignment. There was a small community of American expatriates on St. Croix, and Atti set up an informal school there. Jan attended it until he was ten, when he entered a more established, but still (by mainland standards) tiny school. He left St. Croix for college in 1966, enrolling at Rollins, in Florida, and stayed there for two years, majoring in English. A further three months at the San Francisco Art Institute in the fall of 1968 completed his academic career.

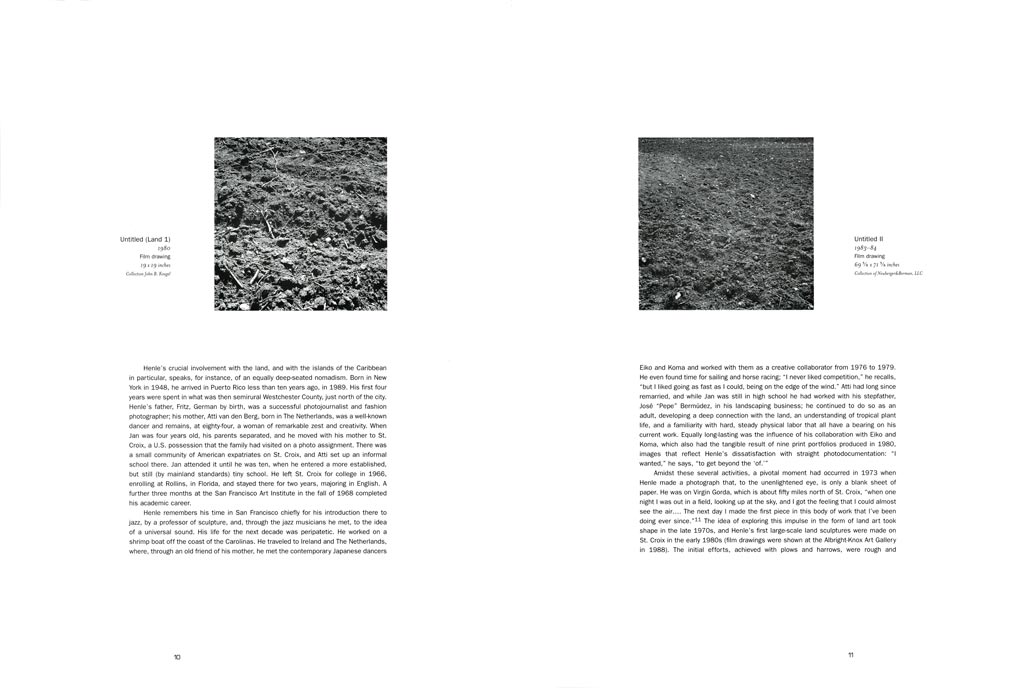

Henle remembers his time in San Francisco chiefly for his introduction there to jazz, by a professor of sculpture, and, through the jazz musicians he met, to the idea of a universal sound. His life for the next decade was peripatetic. He worked on a shrimp boat off the coast of the Carolinas. He traveled to Ireland and The Netherlands, where, through an old friend of his mother, he met the contemporary Japanese dancers Eiko and Koma and worked with them as a creative collaborator from 1976 to 1979. He even found time for sailing and horse racing; “I never liked competition,” he recalls, “but I liked going as fast as I could, being on the edge of the wind.” Atti had long since remarried, and while Jan was still in high school he had worked with his stepfather, José “Pepe” Bermúdez, in his landscaping business; he continued to do so as an adult, developing a deep connection with the land, an understanding of tropical plant life, and a familiarity with hard, steady physical labor that all have a bearing on his current work. Equally long-lasting was the influence of his collaboration with Eiko and Koma, which also had the tangible result of nine print portfolios produced in 1980, images that reflect Henle’s dissatisfaction with straight photodocumentation: “I wanted,” he says, “to get beyond the ‘of.’”

Amidst these several activities, a pivotal moment had occurred in 1973 when Henle made a photograph that, to the unenlightened eye, is only a blank sheet of paper. He was on Virgin Gorda, which is about fifty miles north of St. Croix, “when one night I was out in a field, looking up at the sky, and I got the feeling that I could almost see the air….The next day I made the first piece in this body of work that I’ve been doing ever since.”11 The idea of exploring this impulse in the form of land art took shape in the late 1970s, and Henle’s first large-scale land sculptures were made on St. Croix in the early 1980s (film drawings were shown at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in 1988). The initial efforts, achieved with plows and harrows, were rough and haphazard. In 1983, Henle and two helpers cleared a half-acre plot of land for what he calls a “painted sculpture,” the rich, black surface of which was created with fifty cubic yards of manure. Henle undertook this sculpture because he wanted “less distraction—a monochromatic, minimal surface,” and he recalls its realization as “physically intense.” At first, the manure was spread by hand, from a wheelbarrow with a shovel. It was turned into the ground with a tiller, turned over again at night with shovels—the sculpture “transferred to film” in the early morning, when its blackness was maximized.

The progression to La Jíbarita was fairly direct, though several factors contribute to its distinction from previous work. Henle’s mother and stepfather had moved from the increasingly overdeveloped St. Croix to Maricao, and he shared their enthusiasm for Puerto Rico’s wetter, less populated, and far less tourist-oriented interior. The change in landscape affected the work, as did the different culture of Puerto Rico, as the work relies on collaborative effort. (St. Croix has a large black population of slave descent; Puerto Rico, where slavery was never as dominant, has a significant tradition of landholding peasantry, for whom pride in farming remains very strong. Native populations on both islands were more or less decimated.)

Immediate, local factors are, of course, not Henle’s only influences. He responds with perspicuous sympathy to the work of other artists who have made sculptures in the land, including Robert Smithson, Michael Heizer, and James Turrell. Surprisingly, Henle is fairly tolerant of these artists’ colossal invasions of the Western landscape, observing that, from a larger perspective, Heizer’s Double Negative (1969-70) is “a tiny scratch on the earth;” he also admires the “human quality” in Richard Serra’s work. A bit closer in spirit are the eclectic group of sculptors who have divined the natural essence of organic materials---Henle mentions the wood-carver Raoul Hague, and also Wolfgang Laib, for his careful tending of milk, rice, pollen, and beeswax. But Henle’s deepest sympathy, suggested by his connection to Hague, is with certain artists of the Abstract Expressionist generation. The reliance on Eastern spiritual systems, particularly for framing abstraction as more than a formal problem; the temerity to ask big questions of art; and the self-abnegation (for which, admittedly, heroic claims were often made) involved in accepting partial or provisional answers, are all characteristics he shares with an older generation. Mark Rothko’s immersion in almost animate fields of earth-toned color is relevant to Henle’s work; Willem de Kooning’s published statements---for instance, his reference to content as a “glimpse”---have also intrigued Henle. In terms of thinking if not practice, Henle’s closest affinity among painters of Rothko’s generation, however, may be with the proto-quasi-Minimalist Agnes Martin, who was born the same year as Jackson Pollock but like Henle has inclined (increasingly, in her case) to self-exile from the community of her contemporaries. Also like Henle, Martin has been a great admirer of Chuang Tzu; Henle has high regard for Martin’s own aphoristic writings. Something of Henle’s attitude can be felt in Martin’s radiant pronouncements (“Beauty is the mystery of life! It is not in the eye it is in the mind!”) and equally in her stern jeremiads (“We are blinded by pride. Our best opportunity to witness the defeat of pride is in our work.”). Above all, Henle shares with Martin a commitment to landscape not as subject, and certainly not as metaphor, but as something as akin to a living medium. He especially likes her remark, “when people go to the ocean they like to see it all day…It is a simple experience. You become lighter and lighter in weight, you wouldn’t want anything else. Anyone who can sit on a stone in a field a while can see my painting.”12

In making these comparisons with modern Western artists, it remains to be re-emphasized that Henle’s sculpture is essentially an art that attempts to reveal emptiness. And here, too, useful analogies can be made. “He had defeated the need for sculpture to consist of any additional matter at all,”13 Thomas Crow writes about Gordon Matta-Clark, who worked within a vastly different context from Henle’s, but took a strikingly relevant approach. Carving up the walls and floors of abandoned urban buildings with tremendous aggression and panache, creating arabesques of gloom-piercing light, Matta-Clark used a vocabulary of subtraction to make sculptures that were as spectacular as they were (Crow astutely observes) mostly unseen. (The danger they caused to viewers and, generally, their illegality meant that most admirers saw Matta-Clark’s interventions only after the fact, in photographs.) And that double absence---working by eliminating form, proceeding without visual confirmation except in photographs, and in fact relying on the work’s demolition to consolidate its meaning---is very close to Henle’s current practice. In one notorious 1976 incident, Matta-Clark shot out the windows at the Institute of Architecture and Urban Studies with an air gun, an act perceived by the sponsor as vandalism, and immediately concealed. Crow comments, “the eradication of the piece, which amounted to an instantaneous summoning of resources to repair the damage, actually complete it.”14 The same description could be used to account for the clearing and regrowth of La Jíbarita.

Yet a gulf of meaning again opens wide. Throughout this thicket of comparisons and analogies, an attentive reader will be hearing Henle’s voice repeating, quietly but insistently, no thing. Though its embrace is staggeringly broad (because, perhaps, of the breadth of its embrace) the work is also based in energetic, concentrated withdrawal, not least from offers of artistic companionship, however well-intended. Even closer to the bone is its opposition to language. They may be welcome visitors to his house, but words are, in the end, no real friend to Henle’s work. “Name is only the guest of reality,”15 is one of the more unforgettable epigrams in Chuang Tzu. “If the Way is made clear, it is not the Way,” the writings also say. “If discriminations are put into words, they do not suffice.”16 More emphatically still, Chuang Tzu says, “those who discriminate fail to see.”17 To create a clearing, a light-filled space, where words are humbled and discriminations politely dismissed, is a delicate business, but an admirable one, and hard.

Notes

Michael Auping, Jan Henle: Topographical Film Drawings (Buffalo: Albright-Knox Art Gallery, 1988), unpaginated.

This and all further unattributed quotes by the artist are from discussions with the author, July 1997-January 1998.

Mai-Mai Sze, "The Tao of Painting," in The World of Zen: An East-West Anthology, edited by Nancy Ross (New York: Vintage Books, 1960), 98-99.

Ibid., 99.

Will Petersen, “Stone Garden,” in The World of Zen, op. Cit., 109.

Daisetz Suzuki, An Introduction to Zen Buddhism (New York: Grove Press, 1964), 34.

Ibid., 45.

Thomas Merton, Mystics and Zen Masters (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1967), ix.

Ibid., 13.

Suzuki., 43.

Vincent Katz, "Something on Jan Henle: An Interview," The Print Collector's Newsletter (March-April 1995): 5.

Quotes of Agnes Martin are as follows: "We are blinded by pride...," is from "On the Perfection Underlying Life," 1973; "Beauty Is the Mystery of Life" is from "Beauty Is the Mystery of Life," 1989, "when people go to the ocean" from Ann Wilson's "Linear Webs," 1966, reprinted on pages 26, 18, and 40, respectively, in Agnes Martin: Paintings and Drawings 1974-1990 (Amsterdam: Stedelijk Museum, 1991)

Thomas Crow, "Site Specific Art: The Strong and the Weak," in Modern Art in the Common Culture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996), 133.

Ibid., 134.

Chuang Tzu: Basic Writings, translated by Burton Watson (New York: Columbia University Press, 1964), 26.

Ibid., 39-40.

Ibid., 46.